December 31, 1887

Tonight, in these last hours of the old year, I have been thinking of New Year's Eves at home in the Borders, when I was a child and my father still alive. I remember how the Hogmanay fires burned the old year out, how the midnight bells rang, and how we waited for a dark-haired man to step over our threshold, bearing gifts of coal and salt, black buns and shortbread.

I wonder what they do to welcome the New Year in that great house (as I imagine it) in Wiltshire. Are there bonfires on the downs, and bells pealing out? Perhaps Tom Grenville-Smith is alone tonight, as I am, sitting beside the fire with a book on his knee while he dreams about Brazil. But no, most likely there will be a ball, and it will be waltz music that he hears; and he will dance with ladies in low-cut Paris gowns in a blaze of lamplight, under glittering chandeliers.

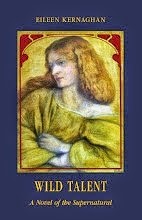

These winter nights when I am abed with the candle blown out and I am drifting towards sleep, I find myself thinking how it would be to leave this cold grey city and live once again among woods and fields: not in a ploughman's cottage as I once did, but in a grand house with servants and many rooms, and one room entirely to myself, with shelves for my books and a desk upon which to write. And sometimes as sleep overtakes me, though I know it is daft to do so, I think of the one person with whom I would wish to share that house -- or any house, be it only a ploughman's cottage after all. (From Wild Talent: a Novel of the Supernatural)

* * *

The moon came out, and flooded the broken snowscape with its chill white light. Never had Gerda imagined a scene so beautiful, or so forbidding. There was something dreamlike, hallucinatory, about this northward journey. Always before there had been lakes and rivers, hills and forests to help them chart their way. Now there were no more landmarks, and the thin shell of ice upon which they walked was like a vast unfinished puzzle, the pieces endlessly lifted and turned and shuffled by a giant hand.

Gerda had not thought it was possible to be so lonely. Though she was grateful for Ritva's steadfast presence, each of them, trudging silently through that frozen world, was locked in her own solitude. Is there anything more frightening, Gerda mused, than to be utterly alone with one's own thoughts? It was no wonder that arctic travellers panicked and went mad.

*

"Oh, look," said Gerda, awestruck, as the black sky filled with swirling ribbons and darting, flickering shafts of rainbow colour. "Ritva, look, the northern lights!"

"Oh, look," said Gerda, awestruck, as the black sky filled with swirling ribbons and darting, flickering shafts of rainbow colour. "Ritva, look, the northern lights!" "I see them, " said Ritva impatiently. She added, with sour irony, "Why are you whispering? Who's going to hear you?" And Gerda realized that her voice was as hushed as if she were in church.

Somewhere in the near distance there was a thunderous crash; the ice shuddered and rocked beneath their feet. Ritva caught hold of Ba's collar as he reared in panic. In the shimmering light of the aurora they saw a huge crack opening up not twenty paces ahead.

An ice-block the size of a cottage thrust halfway out of the fissure, and then slipped back. There was a grinding, splintering sound, and with a jolt the ice tilted sharply beneath them. Suddenly everything seemed to be moving, shifting, eddying. It was as though some huge sea-creature was threshing wildly beneath the ice.

Gerda's heart gave a sick lurch as she watched a black, windbroken expanse of water widening before them. Ever since they had abandoned the Cecilie this was the thing she had dreaded most, the fear that had haunted her restless sleep. They were adrift, at the mercy of wind and tide, on an ice-floe hardly bigger than the Princess's swansdown bed. ( From The Snow Queen)

* * *

All at once the wind died, and the sky cleared, and they were climbing through a jewelled world, transfigured by the evening sun. Every cliff and crag glittered with icicles, topaz and emerald in the slanting light. Ice crunched and splintered beneath their feet. Sangay looked down and saw that the path was striped with shimmering bands of colour -- pale green, white, sapphire blue and ruby-red. They had come to a curtain of ice, suspended like a frozen cataract across the trail. Sangay put up his hands to shield his eyes from the glare of the reflected sun.

Then somehow, in a dazzle of light, they had passed through and beyond the ice-curtain, into a forest of spires and turrets and columns. The air was very cold, very still, and filled with an eerie ghost-green radiance. Sangay could hear only the crackle of the ice under his boots, and the faint whistling of his own lungs. His breath hung before him like pale green smoke.

Now, as Jatsang led him deeper and deeper into the heart of the glacier, the path widened, and there were glistening open spaces among the thrusting ice-spires. The cold green light brightened, was edged with gold like the first flush of sunrise seeping into the sky. And then they had passed beyond the frozen forest and its shrouding wall of ice, and had come to the edge of a summer garden, a green and flowering valley hidden away among the snow-bound peaks. (fom The Dance of the Snow Dragon)

Prayer flags dance in a white dawn.

The wind’s horses leave no track upon the snow.

The voice of the flute

is the sound of a white bird singing.

Night music: beating of white wings

Over frozen water.

Under the ice, moon-bubbles rise.

The fish are dreaming.

(From Tales from the Holograph Woods: Speculative Poems)

No comments:

Post a Comment